Intensification and the urban boundary

You are here

Ottawa’s population is growing. Recently, we crossed over the one million population threshold on the Ontario side, and we are assuming for the purpose of developing our new Official Plan that we will grow to 1.4 million by 2046. That’s coming up fast. My son will be a little younger than I am today in 2046, maybe with kids of his own ready to move out. If you have young children today, many of them will have just left school and will be establishing new households and families. It’s really not that far off.

How we accommodate that growth is critical to consider. In Ontario, cities are expected to have a plan for how they will grow sustainably – an Official Plan – that adheres to Queen’s Park’s orders to municipalities that they focus on intensification, growing most intensively in already-serviced areas of the city and near transit and amenities.

Right now, we’re developing a brand-new Official Plan that will describe how Ottawa will meet the imperatives of that provincial policy. One of the most critical decisions to be made in the course of crafting that will be where to set the urban boundary. That boundary fixes a line beyond which developers won’t be allowed to build new sub-divisions.

The discussion that’s heating up is whether or not to expand the urban boundary. That’s not some arcane planning discussion. Whether or not we continue to allow suburban sprawl will affect the quality of life for our kids and new residents in the city. It is the single biggest decision within the purview of cities in Ontario to make affecting both climate change and the affordability of housing. We all know that urban sprawl is a very bad thing, and few people would seek deliberately to exacerbate it. But I’m writing today to make sure that all the implications of stopping it are clear to residents.

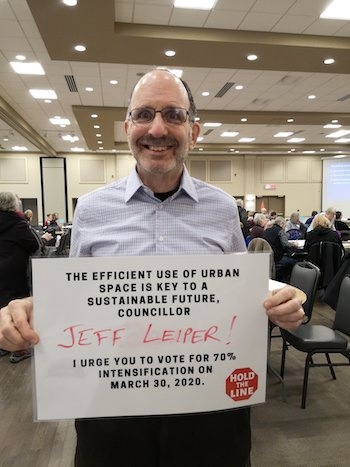

Recently, Ecology Ottawa has begun a social media campaign to press the case with councillors for a target 70% intensification rate in order to mitigate the need to expand the urban boundary. I have tremendous respect for Ecology Ottawa and it’s a snappy campaign. I'm fully prepared to support it, but it's important to understand exactly what it means.

The jumping-off point is that we believe we'll need to accommodate 400,000 new people in the next 26 years. The choice that will likely be before us in March will be to expand the urban boundary by several hundred hectares (an area roughly the size of our McKellar Park neighbourhood) which would mean that 60% of new households will have to be accomodated through intensification. Or, we can constrain the urban boundary to where it is today, which would mean 70% of new homes would have to be built in already-serviced areas. There are pros and cons to either approach.

At this point it's worthwhile to note that I'm shying away here from an in-depth analysis of the numbers. Staff will be presenting in March their quantiative analysis, but anyone who wants to get a jump on that should take a look at the Annual Development Report. The key stats I'll put on the table now are that in 2018 the intensification rate was 55%. For the period 2017-2018, the intensification rate was 47%, and for the period 2012-2016 it was 51%.

Those high-level numbers gloss over some important nuance. The Province has ordered Ontario cities (for all the right reasons) to intensify as a key growth strategy, and they have further refined that by ordering that intensification to occur near transit. Our current Official Plan designates residential target intensification areas that are near transit and employment areas: the Central Area, Mainstreets, Mixed-Use Centres, Town Centres, and the areas 600m from transit stations. In 2018, target areas received 54% of overall intensification (net of demolitions, 2,417 new units), a large majority of that near existing transit stations. Most of that intensification activity in targeted areas has been apartments.

Intensifying in those target areas is critical to address both housing affordability and climate change, and it's why we're seeing so much focus on wards such as Kitchissippi. The point of targeting intensification is to ensure that people live near transit, have short commutes, and can walk or cycle to accomplish many of their daily activities. While we can and must allow intensification of our further-flung suburbs, the wins are smaller in doing so. Replacing a single detached home in Convent Glen with a row of townhomes might make serving the neighbourhood with transit and plowing the streets more economical, but many day-to-day activities such as getting to the library, the hardware store or the gym will still be relatively unattractive except by car without a massive and probably prohibitively expensive (in the near term) re-design and retrofitting of its streets. That's not just an Ottawa problem; municipalities across North America are struggling with reversing decades of car-centric planning.

But to come back to the 60% versus 70% debate, it's clear that either option will require significantly more intensification than we're already seeing.

Some of the focus on wards such as Kitchissippi will be mitigated by the extension of LRT. The area around Blair station is seeing multiple new towers built. The lands east of Place D'Orleans are seeing the same. A big new mixed-use development is being contemplated at Lincoln Fields. Much of that, however, is apartment towers (the focus on rental today as developers respond to the brutally low 1.8% vacancy rate in the city). Of those 400,000 new residents we'll see by 2046 many will, of course, be households seeking more than one bedroom. North American proclivites skew toward low-rise living, with private outdoor amenity space. Demographers tell us that more Millennials and Generation Z will seek to live in smaller quarters, car-free if necessary, in return for living in vibrant urban neighbourhoods. I tend to agree. But, many will want to live in townhomes, semis and low-rise apartment buildings.

All in all it means more towers, more low-rise infill, and the expansion of areas in which low-rise apartment towers (the "missing middle") are allowed to be built. Those will be most intense near transit and employment areas and in walkable neighbourhoods that have shops and services: in places like Kitchissippi. Moving to 60% intensification will accelerate that. Moving to 70% implies a significant increase even over that. As I noted at the outset of this post, I'm fully prepared to support a 70% intensification target to stop urban sprawl. But that does have consequences. We need to make that decision with our eyes wide open.

- Log in to post comments